Postmodern Beauty:

Woman as Object and the Returned Gaze – Is it Really All About the Male Erection?

by: Leah Welch

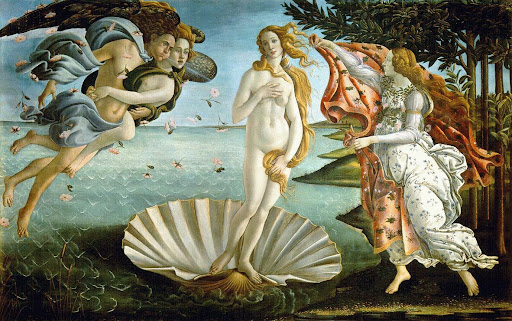

Through each era of art artists have held to a certain canon of beauty: From Venus of Willendorf (24,000-22,000 BCE) to Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1482). This representation was in the form of the ideal woman – the way the statue or painting was rendered afforded the viewer a look into that period’s idea of classical beauty. The stone statue of the Venus had tiny arms across an abundance of breasts thereby indicating that the culture’s focus on woman was her ability to give birth. The small hands were an indicator that this was not an important part of the female body. In Botticelli’s rendering of the Venus the painting characterizes the long torso of that era’s canon of beauty – her wisps of hair and her contrapposto stance (a stance used in a plethora of Greek and Roman statues of men and women and a stance which the Italian Renaissance adopted-a stance that perhaps a postmodern critic may say to be a weak stance, one that does not afford its server any type of ground to make a move on) along with her nude form and the way in which she covers herself but is still not hinting at any shame, is the canon of this era of art. In fact, this stance and this type of beauty remained with the art world up until modernism. The purpose of this paper is to explore the function of beauty in consideration of modern and postmodern photographers: Edward Weston and Cindy Sherman. The approach to beauty and the way in which the female as an entity and as a form is, is depicted in each photographer’s work will be examined along with consideration of the gaze, women as object, fetishism and the male erection.

Weston’s modernist views juxtaposed with Sherman’s more elaborate postmodern themes with her objects/mannequins/models reveal a difference in gazes. It is with Jacque Lacan’s study of the gaze, that psychoanalytic process in which the object knows they are the object. It is through this main psychology that we shall approach Weston and Sherman while keeping in mind Eck’s work on gender:

Men, as previous researchers have demonstrated, view the female body with a sense of ownership (Berger1977). They interpret female nudes as objects of pleasure or derision and by so doing reproduce and sustain heterosexual masculinity on a daily basis. Men's status as "men" is reaffirmed every time they encounter and pass Judgment on the female form…men's responses to the Hartigan nude dismiss her as a potential candidate for desire, quickly labeling the image as "art"-an antiseptic term that removes the body from potential erotic pleasure (Nead1992). When men look at these images, they reveal no sense of embarrassment or self-consciousness in rendering an opinion on these models. They assume a culturally conferred right to evaluate the female nude (Eck 696-697).

In Weston’s work the gaze of the object/woman goes unreturned. The women or object as Weston saw them, parade in his photographs without heads, with covered and shielded eyes or blanketed by another body part. The Spectator is then removed from the fear that they will be caught looking at a nude woman and it is in this voyeurism that fetishism grows. This loss of autonomy by the object pervades through Weston’s works as is witnessed in the photographer having taken over 60,000 photographs, the majority of which are of nudes, and of those nudes the Spectator would be hard pressed to find a returned gaze from any of the objects (McGrath 334).

It must be said that as a modern formalist photographer, Weston was not interested in the female form per se, but rather in the shape of the body. He and his muse, second wife, Charis Wilson, believed the world contained only a strict few perfect forms; “The body of the woman was, for them both, one of only three perfect shapes in the world. (The other two were the hull of a boat and a violin…)” (McGrath 329). Thus the content of the photographer was inconsequential on a conscious level to the formalist. However, this repetition in a large amalgamation of prints suggests that on another level there was intent in choosing such a form for this work. This can be supported through Weston’s own journal in which he substitutes “nude” for “negative”; “In his diary Weston makes the following slip: ‘I made a negative I started to say nude…’” (McGrath 331). The inclusion of this deliberation in his diary may suggest that despite the formalist persuasion of his work the use of female form may have been approached because of the shape but it was Weston who deemed them objects through his vicissitude in terming them objects and his evisceration of their gazes.

This evisceration (which is sidestepped in Sherman’s photographs) is very sexual in its exchange. First, the Spectator sees the object but the object (interchanged with woman) is denied a return gaze. It is this lack of autonomy that further involves the Spectator turning from mere passive person to interactive person. The interaction here is beget with physical penetration: The gaze of the viewer peers ever more ardently since there is no fear of being looked back at, and therefore judged, or even seen. The penetration here is in reference to the penetration of the space between object and Spectator (McGrath 330). The only way that this interchange is made possible is through Weston’s particular style as Operator: “Unlike the woman herself the photograph is portable, can be referred to at will, and is always a compliant source of pleasure. Without this scenario the camera is another device of denial and retention” (McGrath 331). In fact, it is the camera that plays as an interlude between photographer and object that is the true arousal apparatus. It is the camera that transcends the Spectator from passive to aggressive in this gaze/nongaze exchange: It is a fetish device. As such, Weston’s photographs can be seen as pure pleasure and as blatantly sexualized as Sherman’s work tends to be; Weston’s work is far more pornographic because of this allure of the unreturned gaze and the lack of repentance from the voyeur.

Woman’s deconstruction of self, her lack of autonomy, is what marks Weston’s work; that is, her physiognomy robs the viewer of enjoyment of the object (woman); for as McGrath states, “If the face appears, the picture is inevitably a portrait and the expression of the face will dictate the viewer’s response to the body. This would interrupt…the aesthetic appreciation of naked beauty” (328). This masking, prevalent in all of Weston’s nude work is exemplified in Nude 1923 in which a woman lays supine on what appears to be concrete. The startling aspect of this photograph is that unlike many other Weston photographs, the face is intact. The Operator has not cut off her face from her body so that the Spectator receives a more formalist view of the object; nor is her physiognomy hidden by a limb, nor is she face down. This startling aspect of the photograph marks this one as slightly different from the others, but in the essential qualities of Weston’s work, and the qualities that mark the work as fetish, this photograph stands in line next to the others. The same formations of gaze, masking and avoidance of power are the motif that runs strong in this image. The object’s eyes are closed, and her legs are cut off at the knee. In fact, an interesting thing to note about Weston’s work is that the model while not returning the gaze, is often times cut: Either the head or the legs are absent from the full frame of the photograph, or else, if the model is in full view, the camera has panned back so that the viewer receives a larger portion of the landscape than of the model (an exception to this is Nude 1936). In this way, Weston disavowals woman as entity – a thing, an object, an Other. His cutting of them is a symbol of his denial of knowledge to them. They are not permitted to return a gaze, although they are full aware of their own nude presence; they are only permitted to cover up their eyes or their face. This way, the voyeur can look on in their penetrating fashion without being judged. This is the fetishism of his work – his allowance of fantasy. The fact that the women know they are being gawked at but pretend not to know, leads one beyond the proscenium of the stage Weston constructs. What is alluring to this fact and what supports this theory of fetishism, is the sole lack of males in Weston’s body of work – not only of males but of self-portraits. His denial of woman’s gazes is extant with fetishism because of the lack of a male presence in all of his nude work (McGrath 335). In short, Weston’s body of nude work may also be a large body of different and subtle examples of sadism.

After this dialogue on Weston’s approach, it can be stated that although he finds the female form one of three perfect shapes, it is not the female in that equation that is his attraction – rather it is her shape, and in this twist of formalism, in this modernist’s work, beauty finds no canon. Since it is the object of the photograph and not the gender or femininity that excites and lures the photographer into his station, how then can the Spectator expect to find pulchritude in a piece? If the photograph is absent of beauty then the only thing left in the photograph is the sex that Weston gives us – and not the gender, and not the act, but the pervasive penetration of space that remains.

In opposition to Weston’s portrayal of women, Cindy Sherman offers a postmodernist approach to the gaze and to the masking/unmasking of the woman as object. In fact, Sherman uses objects in her photographs. It is this distinction that gives her a philosophical edge to her work. Here the Spectator is presented with the real and unreal. Up until this point the female body was seen as beautiful according to a set rule of what beauty is, as defined by the canon. Even in Weston’s work, despite the invasiveness of the camera and the deconstruction of women through the lens, his photos by many are perhaps illustrative of that canon, for his work does still depict the female form; nude, and in repose. In this regard it echoes many art movement’s view of what beauty is or should be. In Sherman’s work (not her film stills but the work she accomplished in the 1980’s with use of mannequins) the Spectator is presented with what many may not consider beauty by classical standards but forms that mark women as powerful since the objects (mannequins in most but Sherman does make appearances in some of her 1980’s photographs) return the gaze and it is in that act that women gain ground (women are no longer stuck in that powerless contrapposto stance). The canon of beauty here is being redefined so that the focus is less on a taught viewpoint on what beauty is and more about women as powerful and thereby beautiful through their power (in regards to taking back the gaze).

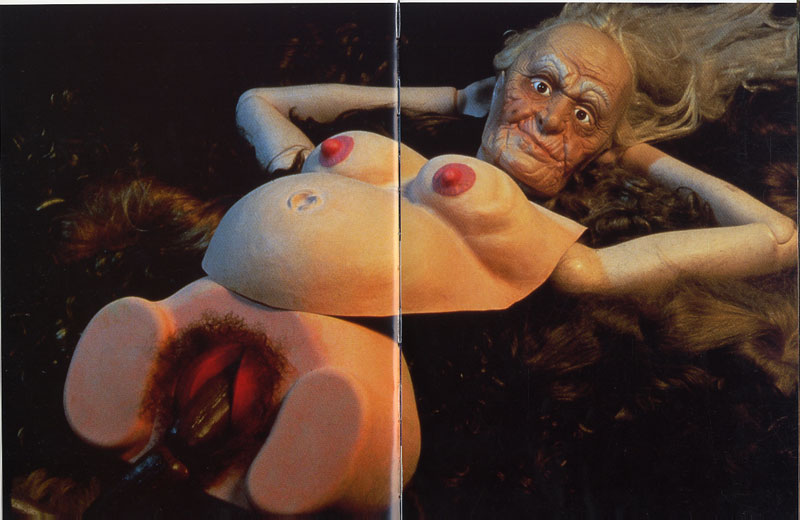

Through the use of mannequins Sherman is already castrating her audience from any penetration into her frame or space. This lack of real flesh allows for Sherman to more effectively control how the Spectator views her work. As she adds distance between the Spectator and the object through a returned gaze and use of fake flesh (Avgikos 339). Thus, the Spectator is unable to immerse into the fantasy of the scenes that are going on inside the frame. This is best exemplified through her Untitled #250 in which a mannequin is lying on top of wigs, with an old woman’s head, what’s present of her legs in spread eagle, a full bush and a dildo/sex toy placed into her vagina: “…Medusa/whore/Venus/Olympia, who menacingly displays her startling red-foam vagina, the invitation promising pleasure for herself alone” (340). The head of the mannequin is unabashedly looking out of the frame of the photograph straight on into any and all Spectators. This brazen look is filled with a backlash of …well, of power. For ages, the woman in art has been the other, the object, the thing without knowledge. And yes, thing is the operative word. In Sherman’s work however, despite the presence of fetish items their place in the photograph only serves to strengthen this idea; the mannequin is looking at us saying, you wanted to see, so go ahead, take a good, long look.

This positioning of the mannequin denies the viewer power over the object – over the woman that this mannequin stands in place for. The object is in full awareness (as well as the Operator) that someone is looking at them and instead of hiding their face and pretending to not know they are being looked at as in Weston’s photos, Sherman’s mannequins stare back: In this stare it is Sherman’s gaze that the Spectator is seeing, “This argument fails to take into account Sherman’s control as director and producer of her own visual dramas” (Avgikos 341). In this fashion, Sherman is not allowing the Spectator to gain an erection nor is she suggesting castration with her missing limbs (a commentary that perhaps has more to do with how the gaze has not only left women without autonomy but has left them with parts of themselves missing) instead this indelible gaze gives back women their face, their self, their identity. It is through her fetishism that she castrates her viewer for gazing with sexual intent into her work and it is ultimately them she mutilates – a penitence for having sinned as they have (not speaking here about sex but about stealing a person’s soul/identity); As Avgikos states, “Sherman’s representation of female sexuality, in contrast, indulges the desire to see, to make sure of the private and the forbidden, but withholds both narcissistic identification with the female body and that body’s objectification as the basis for erotic pleasure” (340).

This desire to see stands as stark contrast to women as Other – of women being denied the gaze back into the Spectator. By denying the classical beauty that Weston held to be true (of the female form being one of three objects that were perfect in this world) – Sherman allows for female identity and in order to do that she must break the previous well-established, patriarchal canon of beauty - she must mutilate this female artifice in order to give her power: She must destroy the idea of male beauty in order to reinvent female beauty.

Avgikos coins a term in her essay “active looking”. This means that the model is not passive – that is, is looking back into the audience. In Weston’s photos, the object was denied knowledge through covering her gaze - juxtaposed with this is Sherman’s active looking models who in their gaze fulfill a self-satisfied pleasure, “In Sherman’s photographs, however, active looking is through a woman’s eyes, and this ambiguity makes them both seductive and confrontational…Sherman heightens the spectacle of the sexual act by isolating genital parts and coding them with fantasies of desire, possession, and imaginary knowledge” (339). This idea of possession takes us back to Weston’s photos in which the Spectator possessed the space of the object. The knowledge that Sherman infuses into her work is beget through fetish – through dildos, open vaginas and in these items and ‘body’ parts we find a plethora of cerebration: “The instrumentality of these photographs lies in their tantalizing paradox: offering for scrutiny what is usually forbidden to sigh, they appear to produce a knowledge of what sex looks like… but simultaneously are not real” (339).

Another interesting item in both of these photographer’s works is that while Weston exhibits a complete absence from his work, Sherman is very much present in hers. Sometimes taking the role of the model as in her film stills or sometimes taking the role of a mannequin as in her work Untitled 305 in which she poses as one of the mannequins. Even with this presentation of real flesh however, because the model is designed to represent a mannequin the idea of castration through fetishism in Sherman’s work still stands, “Her mechanisms of arousal – rubbery tits, plastic pussies, assorted asses, dicks, and dildos – may deceive momentarily, but finally defeat the proprietary gaze of the spectator, whose desire can only partially be satisfied by the spectacle of the artificial flesh” (340). Through these devices women reclaim their identity through centuries of being objectified through the patriarchal male canon of beauty; “Helene Cizous insists that women should mobilize the force of hysteria to break up continuities and create horror. This is not to hark back to some ‘natural’ state – an effort that masks woman’s censored hysteria as though it were an unwelcome disease – or to fall into some other form of ‘political correctness,’ and the guilt and repressed desire that it triggers…Rather than making a ‘sex-positive,’ Edenic retreat from that which we think we should not think or do, Sherman complicates libidinal desire” (341). This invitation of welcoming hysteria is what dominates Sherman’s frame – all of these mannequins in sexual positions and blatant fetishisms are a pleasure that is not translated for the Spectator but is for the mannequin alone.

The lack of a gaze in the classical canon is misinterpreted as reverence. The female looks away from the viewer, or hides her body in order to detach herself from her humanity, from the thing that makes her human, that makes her a woman. The gazes presented in these two photographer’s works are set on two sides of an era: Modernism and postmodernism. Modernism’s goal is to document what is real, what is around them – on a subtler contextual level this may be interpreted to mean we must discern fact from fiction when viewing Weston’s nudes. The fact is, is that he termed them objects, turned them into negative nudes and denied them faces not solely so the form of their body isn’t compromised by presenting physiognomy in the frame but so that the Spectator can view them in uninterrupted passion and eroticism through fetish and voyeuristic clandestine nature. In postmodernism we are struggling with authorship – in presenting mannequins instead of people Sherman is stating that there is no authorship and because of that we are liberated to view whomever and however we want. There is great sexualized energy in one and great liberation in the other photographer. Both veer toward fetish and both re-evaluate our ideas of the canon but neither one sticks with the classical canon as a way to see the female form. It is interesting to note that Simone de Beauvoir states that a woman is not made, she is born – in effect, the object/model is diverting her gaze because of something that is not innate but is learned and it is strange to think that in Weston’s work this aversion shows lack of knowledge when in looking away from the camera the woman is telling the Spectator that she knows she is a woman. There is no gaze that can deny that fact.

Images:

Venus of Willendorf, 24,000 B.C.E. - 22,000 B.C.E.

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, c. 1485-86

Edward Weston, Nude, 1923

Edward Weston, Nude, 1936

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #250, 1992

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #305, 1994

References

Avgikos, J. (2003). Cindy Sherman: Burning Down the House. Ed. Liz Wells. Routledge.

London.

Eck, B.A. (October 2003). Men Are Much Harder: Gendered Viewing of the Nude

Images. Gender and Society, Vol. 17, No. 5, pp. 691-710.

Source: McGrath, R. (2003). Re-reading Edward Weston. Ed. Liz Wells. Routledge.

London.

No comments:

Post a Comment